COP25 & Spain’s Involvement

Hosting COP25 is an excellent opportunity for Spain to showcase progress made on the energy transition since the socialists (PSOE) came to power in June 2018. Spain’s Minister for the Ecological Transition, Teresa Ribera, is determined to use the COP to advance both international and domestic action on climate change. After years of stagnation in renewables development under the previous government, Spain now has a lot to share with the world.

Why Madrid?

Spain agreed to host the 25th Conference of the Parties (COP25) to the UN’s climate body when Chile pulled out due to the civil unrest that erupted in October in Santiago and many other major cities throughout the country, resulting in at least 20 deaths and heavy-handed police crackdown. While Chile continues to grapple with the unrest and forge a new post-Pinochet constitution at home, it retains the Presidency of this COP and will co-host the meeting with Spain. It means Chile and Spain will co-host this COP, as the Latin American country is retaining the Presidency of the meeting. This is not unusual: in 2017, Fiji hosted COP23 in Bonn, Germany, as it lacked capacity in its capital of Suva.

Spanish Energy Mix

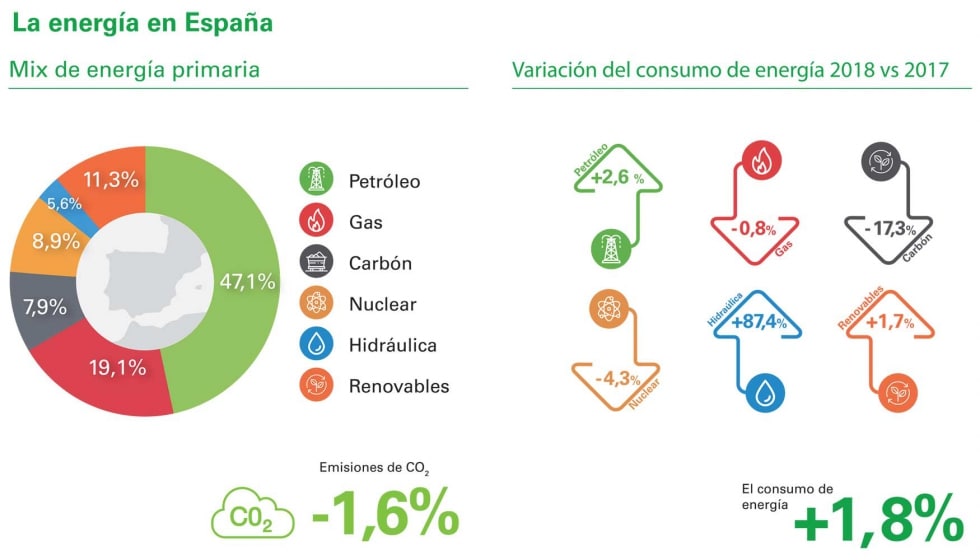

Spain is quite dependent on fossil fuel energy. Even with steady renewables growth in recent years, Spain still sourced nearly three-quarters of its energy from coal, oil, and gas in 2018. While the country’s energy consumption increased by 1.8% from 2017 to 2018, carbon emissions decreased by 1.6%, mainly due to a massive increase in hydro resources. Over the previous year, Spain’s emissions had increased by the highest margin in five years. From 2017 to 2018, Spain saw a modest increase in consumption of renewables and oil, a slight decrease in gas, and a large 17% decrease in coal.

Spanish primary energy in 2018, and % change from 2017 (from Redaccion Interempresas using BP data)

Spain is the sixth-largest energy consumer in Europe, and the seventh-largest consumer of natural gas. Spain has virtually no domestic production of oil or gas, so relies completely on imports of these fuels. Government regulation prevents sourcing too much from any one country, making Spain the most diversified importer of oil and gas in Europe. However, Spain has significantly more gas infrastructure than it needs, as revealed by this recent investigation. Its six LNG regasification plants and several pipeline systems can process more than twice the amount of gas than its domestic demand as of 2015. So far in 2019, Spain’s gas plants have been running at only 24% capacity, while new projects continue to be built.

Looking forward, Spain has massive potential as a global leader in renewable energy. The 2019 Bloomberg New Energy Outlook labelled Iberia as ‘gold standard’ for renewable investment. With abundant wind and solar resources, and companies such as Iberdrola showing leadership in renewables production and expansion, institutional investors look to Spain for high returns.

Climate Action in Spain

Before the Sanchez government, the conservative Partido Popular was in charge and climate action stagnated in Spain. They cut back on subsidies for renewables, creating an effective moratorium. In addition, they instituted a “sun tax” on self-consumption solar PV systems, which required owners to pay an additional tax on the energy they produced and used themselves, while requiring that owners of systems under 100kW donate any extra energy they generated but didn’t use back to the grid for free. This change in policy created deep uncertainty and setbacks for the rooftop solar industry, halting installations for three years. The increased ambition on climate change in the European Union overall did not seem to be influencing Spain.

In June 2018, Pedro Sanchez of the socialist party (PSOE) became Prime Minister, providing an opening for significant climate action in the country, especially with the appointment of climate expert Teresa Ribera as Minister for the Ecological Transition. Under her management, the government abolished the “sun tax” and encouraged the development of community solar. With Sanchez and Ribera’s leadership, Spain has also become a leader in ensuring a just transition, starting with their agreement to close all coal mines last year, signed by all unions. From the top down, there has been a clear commitment to ‘leave no one behind’, and the government has continued to work with affected communities to ensure that coal closures are compensated by growth in the clean energy economy.

In February 2019, the Sanchez government released their latest draft climate package, which aims to make Spain carbon neutral by 2050 by encouraging an effective phaseout of coal and achieving 74% renewable electricity generation in 2030. If passed, Spain will plan to reduce emissions by 21% compared to 1990 levels by 2030. This is less than the current EU target of 40% but is in fact a similar cut as current emissions are 18% above 1990 levels. Nevertheless, NGOs criticise the ambition as being inadequate for the scale of the problem, and if the EU increases its ambition to 50% cuts for 2030, then Spain may have to re-evaluate its plan.

Meanwhile challenges abound for the current proposed plan, including the need to attract almost €200m of private investment over the next five years to implement the plan. Parliamentary passage of the law has been stymied by the failure to form a government since elections in April, but it is hoped that one will be formed by early 2020 and the energy package can be seriously considered. In addition, a combustion engine ban was originally part of Spain’s draft plan, but was later removed after receiving severe pushback from the country’s association of automakers. The natural gas lobby also continues to hold political influence in the Spanish Parliament and across the European Union.

Current Politics

Spain, meanwhile, is working to put together a new government, their second in just over six months, with uncertain implications for climate policy. In the April elections, the Socialists still won the most seats out of any political party, but failed to secure a majority and therefore form a government. This turned Pedro Sanchez into the “acting” Prime Minister and has stalled progress on legislation, including the draft climate package. Sanchez tried to make a deal with the left-wing Podemos party, but these talks collapsed and they were unable to meet the September deadline to form a new government.

The November elections were a strategic mistake for Sanchez, who lost 3 seats, but is now moving quickly to ensure a progressive government. The elections also resulted in a surge in the far-right party Vox, whose leader Santiago Abascal is decidedly anti-immigrant, has denounced the left’s “freedom-killing laws,” and has called anthropogenic climate change a hoax. Vox won more than twice the seats it had in April, much of this due to the growing separatist movement in Catalonia. But Spain’s three right-wing parties did not win enough seats to band together to form a government, which would have been disastrous for climate action.

Now, the Socialists need to attract additional support from smaller and regional parties to gain the numbers to be voted in. Tensions with Catalan pro-independence leaders make this tricky, but after so many months of uncertainty and lack of government there is a consensus that further delays are intolerable and hopes that compromises will be reached. Sanchez and Podemos came to the table again 48 hours after the November elections, and this time were able to strike a tentative deal to form a government that would be controlled by the left. Both the Socialists and Podemos remain supportive of urgent climate action and of advancing a national climate package, which bodes well if they are able to finalize the deal.

And even though the socialists lost seats overall in this year’s elections, they have held or even increased their share of the vote in areas affected by coal mine closures. This is a testament to the party’s “just transition” strategy as well as the high public concern on climate change in Spain across the political spectrum.